Actualization of environmental justice for Indigenous Peoples: How the Philippine-Egongot Tribe stands up for Sustainability and Food Security

This article has originally been published in German on Suedostasien.net on 17. May 2020

Indigenous peoples worldwide are fighting for respect, acceptance and recognition of their land and sea rights, including the Philippine Egongot tribe. Asserting ownership on their legal Ancestral domains requires controlling resource access by outsiders and sustainable management of old-growth forests and coastal areas for tribal food security.

The Flow of Life

Enhancing the flow of life (Daloy ng Buhay in Tagalog) in ecosystems and to create healthy and fair living conditions according to environmental justice, is the goal of the NGO Daluhay, based in the Aurora Province town of Baler on the NE coast of Luzon Island.

Protecting sustainability and safekeeping tribal and artisanal ecosystem use enables the mitigation of global climate change. Daluhay is concerned with the intrinsic networking of ecosystems and the sustainable integration of people. Based upon broad national/international Indigenous experience, Daluhay recently worked as a catalyst with the Egongot tribe based in the Municipality of Dipaculao to help actualize environmental justice on their Ancestral Domain. The Daluhay ‘lens’ includes Ethnoecology (people as part of the ecosystem), Ecosystemics (change for ecological sustainability) and Ecohealth.

Impaired Ecohealth

The scientific branch of ecological health, or Ecohealth interweaves ecology and human well-being. This transdisciplinary approach was developed at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and is recognized by the World Health Organization (WHO). One branch of Ecohealth is looking at an ecosystem-based approach to health, which means in particular the jumping-over of pandemic-causing pathogens from wild animals to humans. Daluhay’s focus is on the complementary health-based approach to ecosystems and tries to find a balance between eco-centric and anthropocentric efforts. Daluhay uses pioneering programs to counter the poor environmental health conditions in the Philippines. Similar conditions have been linked to the emergence of SARS, H7N9 in China1. COVID-19 is yet another global consequence of human intrusion into the world’s last wild natural areas, and has direct implications during the community quarantine in March and April 2020 during the time this article is written.

The precautionary principle is more important than ever as an essential basis for social well-being and ecological health. To translate the ideas of ecosystem into reality, Daluhay promotes the understanding of ecosystem changes and their effects on human health, which are translated into innovative, practical and natural solutions. The NGO takes up these points in their work as a catalyst and supports the Indigenous and traditional people, such as the Egongoty of Dipaculao, in their sustainable development to protect their ecosystems through capacity building, the formation of their autonomy and self-determination. The traditional knowledge and practices of Philippine Indigenous peoples such as herbal medicine and sustainable food security is a real treasure trove of information and directly connected to the archipelago’s life-supporting ecosystem functions.

The Sierra Madre Mountain Range – A global refuge for biodiversity

The country with the highest Biodiversity hosts the last non-fragmented primary forest in Sierra Madre Biodiversity Corridor (SMBC) the Philippines. Around 400,000 hectares stretch over ten provinces. The SMBC is home to over 400 wild species and thus globally significant for a wide range of endemic plants and animals2,3. Numbers for plants, mammals, reptiles and birds are thought to be underestimated and the potential for research is very high. The various Indigenous Peoples in the SMBC use the natural resources for their everyday life. Daluhay works with both the historically nomadic Dumagat and the more agricultural active Egongont, both own certified land titles in their Ancestral Domains3. Their way of life is deeply interwoven with nature. Shifting Cultivation or kaingin (slash and burn) still plays a big role. But the Egongot tribe has adapted this part of their practices to a more environmentally and climate-friendly strategy, now protect old-growth forests and convert kaingin areas into gardens and farms4.

Indigenous People and the influence of modernization on their health status

Acculturation (subtly forced cultural adaption), modernization and the migration of other Filipinos have left their mark on many tribal domains. Both Dumagat and Egongot now have to compete with outsiders and tourism for their natural resources and have to fight illegal logging purposed for hotel construction, and poaching of wild animals3. Forced more into settlements through municipal codes and to gain access to national health and education services, marginalized Indigenous groups are experiencing deterioration in their health. They often suffer from increased morbidity and mortality, which include more frequent infections of the lungs, gastrointestinal diseases and other non-specific diseases5.

Where the wandering and semi-sedentary communities traditionally drank from clean mountain streams, they now often share a water pump or a shallow well. Pollution from the environment due to the lack of sanitary facilities, keeping animals close by and attracted, disease-transmitting rodents are responsible for an increased frequency of viral and bacterial pathogens as well as infections with intestinal worms5.

Food Security and persistent malnutrition

Similar to all coastal communities across Southeast Asia, marine fisheries are critical for this Egongot Tribe’s food security. Fishing provides protein for Filipinos, representing at least half of the animal protein intake6, more so in coastal areas. Industrial and illegal overfishing reduce the Ecohealth for poor sections of the population having direct consequences for their quality of life7.

Peoples dependent on fisheries are further disproportionately affected due to factors such as variable income, land ownership, debt and financial capital, education and, in addition, seasonal and extreme climatic events8. Additionally, Indigenous peoples and small-scale fishers rarely have access to or financial means for health care and medication.

For example, the community quarantine due to COVID-19 in March 2020 already caused food shortages after the first two weeks among the poorer residents in the municipality of Baler, a phenomenon widespread throughout the country due to economic restrictions and constraints in the transport system. In the spirit of Bayanihan (communal reciprocal help) in the wider Philippine community, the shortages are marginally relieved through donation efforts.

The effects of malnutrition are particularly evident in children. Their health status is also used as an investigative factor for the socio-economic status of households9. Protein energy malnutrition is one of the four main malnutrition disorders in the Philippines, causing stunting, wasting and high death rates among infants and children and has not improved over the years even with national strategies9,10. One way monopolizing industries tackle malnutrition is the fortification of foods with vitamins and minerals. However, they regularly fail to acknowledge their own destructive processes to both the environmental and health by suggesting the problem is solely due to unhealthy eating habits, given their focus on maximising profits.

A balanced Ecohealth approach is needed to combat the problem of food security and connected malnutrition over the long-term, much more than just a medical treatment approach.

Implementation of holistic strategies for sustainable Ecohealth

Precautionary management of natural resources under a holistic Ecohealth approach is a sensible long-term path forward. Applied on a global scale, it may also be linked to the prevention and limitation of further disease outbreaks. Mitigating justice strategies must be enforced locally, based upon tenurial rights and modern management plans that link to national and international law.

Increases in terrestrial and marine protected areas under the management of local and Indigenous tribes are encouraged and supported worldwide by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Biodiversity Convention, which agreed on the Aichi-goals and is strategically responsible for global species protection11. The Philippines protect Indigenous cultural heritage through the Indigenous People’s Rights Act (IPRA) which came into force a decade before the United Nations Declaration on Indigenous Peoples’ Rights in 2007.

This Philippine law empowers Indigenous Peoples to legally manage their tribal domains. With the help of the National Commission of Indigenous Peoples, claims, land titles and property certificates are issued to regulate access to tribal domains.

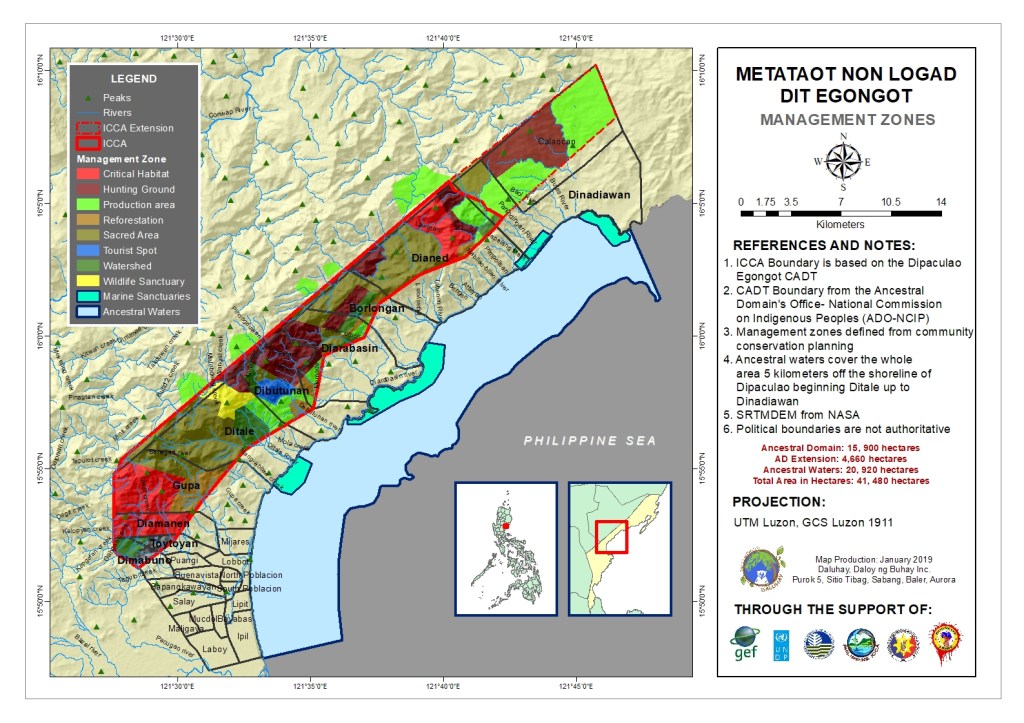

Seven Egongot-settlements exist in the Municipality of Dipaculao in Aurora, which initiated the Indigenous- and community-based conservation areas (ICCA) project together with Daluhay. At their request, the NGO supported them in the management of their Ancestral Domain. Daluhay worked with each of the seven individual Dipaculao-Egongot settlements and the municipal tribe as a whole to delineate and describe a modern land-use plan that would optimise food security and ecological sustainability goals. In practice, however, there is a lack of legal assertiveness due to low levels of political and financial capital. Daluhay works as an intermediary and catalyst between these worlds, identifies principle-centred synergies that link Indigenous, traditional and local to national and international sustainability concepts.

Solution: Nature reserves and local economic initiatives in Indigenous hands

The Dipaculao-Egongot received the certificate for their Ancestral Domain in 2003 and with 15,900 a part of a larger Egongot title which extends across Aurora to Quirino and Nueva Vizcaya provinces with total of 139,000 hectares.

As part of the ICCA project, inventories of forest and marine resources were carried out together with the Egongot for the first time in 2016. The Indigenous people combined their traditional knowledge with international methods and standards and were ultimately able to harmonize the plans with national and local Filipino law.

The factual and objective data base generated identified opportunities for improvement, such as development plans for biodiversity-friendly social enterprises, adapted to the needs of the respective settlement. Using geographic information systems, the inventory of endemic and protected plant and animal species in the rainforests around Dipaculao were quantified. Destruction by illegal practices including logging, charcoal production, slash-and-burn farming and wildlife hunting were also documented. The inventory in the coastal and marine region revealed a decline in fish, as fishermen from other communities, provinces and even other countries are in the waters illegally and use unsustainable, desctructive fishing gear3.

Through the final formal declaration of their community-based nature conservation areas and plans in Dipaculao in March 2019, designated hunting areas, farmland and fishing areas can now be delineated, better managed and defended in the future, and water catchment areas and important habitats for vulnerable animals can be potentially protected.

In addition, the Egongots are now legally recognized as social entrepreneurs under the Dipaculao Egongot Tribal Association12. Motivated by the common success, biodiversity-friendly social entrepreneurship and food security initiatives were initiated not only in one, but in seven different settlements with Daluhay’s support.

One planet, one future

The case of the Egongot tribe and their will to stand up for their social environmental justice is not an isolated case in the world. While humanity is struggling through social distancing in a Pandemic that is spreading at an unprecedented level, this planetary momentary pause is an opportunity to assess the root of the problem. From time since humanity rising, Indigenous People have raised concerns about the outbreak of pandemics and highlighted the irreplaceable importance of the role of ecosystems13. Now is the time to recognize these immemorial values – and to find common way of implementing solutions as a global community. Daluhay plans further holistic strategies with different Indigenous tribes to enforce environmental justice, protect and conserve biodiversity and resources.

About the author

Isabell Jasmin Kittel. Growing up as German-Filipina in Upper Bavaria, her childhood was filled with stories from her mother about the Philippines and life on a small island in the Visayas. Years later as a studied resource manager and tropical ecologist, Isabell Jasmin Kittel explores her own cultural legacy and is currently working on a voluntary basis as part of the NGO Daluhay (Daloy ng Buhay). Apart from co-authoring this article, together with Daluhay’s founders and lead scientists Dr. Marivic Pajaro (Mindanao, Philippines) and Dr. Paul Watts (Canada) she is working on internal capacity building to aid the team protecting the sustainable development of Indigenous cultures, small-scale fishers and the world’s important biodiversity resources via large-scale ecosystems.

Visit www.daluhay.org – also on Facebook.

References

1. Watts, P., Custer, B., Yi, Z.-F., Ontiri, E. & Pajaro, M. A Yin-Yang approach to education policy regarding health and the environment: early-careerists’ image of the future and priority programmes. Nat. Resour. FOrum 39, 202–213 (2015).

2. van der Ploeg, J., Masipiqueña, A. B. & Bernardo, E. C. The Sierra Madre Mountain Range: Global Relevance, Local Realities. (2003).

3. Amatorio, R. et al. Egongot Tribal Development and an NGO as a Catalyst for Sustainability. Fourth World J. V19, (2020).

4. Ramos, B. V. The Ilongot of the Philippines: Indigenous Knowledge and Practices on Education, Climate Change Adaption, Health and Long Life. in Documentation of Indigenous Knowledge and Practices on Health, Education, and Climate Change of Major Indigenous Peoples (IPs) of Northern Luzon (2016).

5. Minter, T., van der Ploeg, J., Pedrablanca, M., Sunderland, T. & Persoon, G. A. Limits to Indigenous Participation: The Agta and the Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, the Philippines. Hum. Ecol. 42, 769–778 (2014).

6. Mohan Dey, M. et al. Fish Consumption and Food Security: A disaggregated Analysis by Types of Fish and Classes of Consumers in Selected Asian Countries. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 9, 89–111 (2005).

7. Añabieza, M., Pajaro, M., Reyes, G., Tiburcio, F. & Watts, P. Philippine Alliance of Fisherfolk: Ecohealth Practitioners for Livelihood and Food Security. EcoHealth 7, 394–399 (2010).

8. Capanzana, M. V., Aguila, D. V., Gironella, G. M. P. & Montecillo, K. V. Nutritional status of children ages 0–5 and 5–10 years old in households headed by fisherfolks in the Philippines. Arch. Public Health 76, 24 (2018).

9. Kreißl, A. Malnutrition in the Philippines – perhaps a Double Burden? J. Für Ernährungsmedizin 11, 10 (2009).

10. Department of Health, National Nutrition Council. Philippine Plan of Action for Nutrition 2017-2022. (2017).

11. Shukla, P. R., Skea, J., Calvo, E. & Buendia, V. Climate Change and Land: an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification and degradation, sustainable land management, food security and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems. (2019).

12. Dipaculao Egongot ICCA, Philippines. ICCA Registry http://www.iccaregistry.org/en/explore/Philippines/dipaculao-egongot-icca (2019).

13. Gilpin, E. COVID-19 crisis tells world what Indigenous Peoples have been saying for thousands of years. Canada’s National Observer https://www.nationalobserver.com/2020/03/24/news/covid-19-crisis-tells-world-what-indigenous-peoples-have-been-saying-thousands-years (2019).

Well well well said! I appreciate how you were able to tackle the areas of the crisis we’re facing and how Indigenous practices can prevent another disease or restore our planet. It really is time to value these practices!! Thank you so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person